In the world of agile sometimes dates matter, hold on let me finish. The day something goes to production should not be considered firm until closer to delivery. Stakeholders consider a date the date, but in reality, they are really hard to set. They are based on estimates, based on a feeling of difficulty months before a project is actually ready to even start development. Dates can even be set by people outside of the development team. All of this could make you want to just not use dates at all.

However, dates help drive the all-important development cycle. They help shorten the feedback loop and let stakeholders know when to expect a new feature. Sometimes agile teams don’t think they have to actually commit to a delivery date. They are committing to work within a two-week time period. Why should they commit to something longer term than that? I worked with a team many years ago that resisted providing dates on anything. They just wanted to do work, which made it hard to plan anything and report on budgets. As their Product Owner, it took a lot of my time trying to understand when things would get done. It wasn’t about the quality of their work, which was good, it was that I couldn’t communicate to stakeholders when things would be done.

Dates matter for all teams because they set expectations. They matter because other teams are counting on the work being done. They are communicated to external users or clients. Dates end up being promises of future work. The team I mentioned earlier was breaking the “contract” with stakeholders. It got to a point that no one expected the work to be done.

Setting a date is the hardest part of actually delivering on the development. There is the grooming process where the team reads the stories and makes a guess to the difficulty of the story. Notice I didn’t say how long the story will take to deliver. Also I said guess; estimates are inherently wrong by their nature. They are based on a best guess without looking at the code or doing any research into what would need to be added. I had a team consisting of a few younger developers with no previous agile experience, and the idea of difficulty vs time was a struggle. It is a foreign idea, and many people don’t understand the why or the benefits of doing story pointing. It seems easier to just say it is going to take two days or one sprint.

In an agile environment, an estimate is a measure of difficulty not a measure of time. The reason stories are measured in difficulty is because it smooths out the differences between developers’ skills. Sometimes the work is done faster than an estimate; sometimes the work is done slower. The team works in estimates of difficulty, but the stakeholders are expecting a timeline for delivery. How exactly do we take an estimate of difficulty and turn this into something a stakeholder can count on?

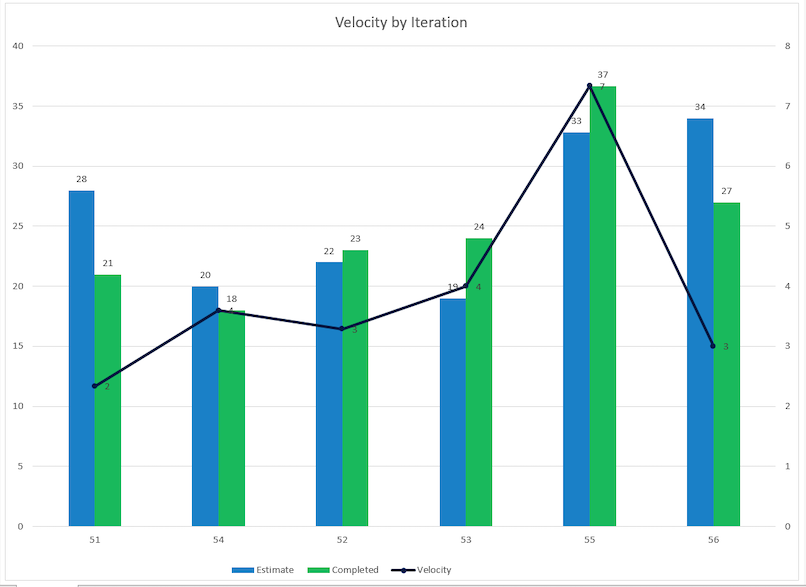

Enter the velocity concept. Velocity is a measurement of the number of difficult stories that can be done during a specific duration. Duration gives you a time period that gets to the root of the issue. What is the due date? The only issue with this calculation is it is all based on a guess. This means that sometimes even with the best efforts, an estimate is off and one (or more) extensions are needed. As a team, what can we do to limit the moving of delivery dates based on an estimate?

Software development teams could be allowed more time to do a proof of concept (POCs), also known as spikes or research, to test out and try the ask. This would allow for better estimates, but how much time do you allow for doing POCs? By spending this time early on, teams can learn some of the unknowns and turn them into knowns. This reduces the risk of bad estimates and depending on the POC, some of the work can be reused which helps reduce the overall time and complexity.

There needs to be some balance between doing POCs and only using the grooming estimates. This is where a Product Owner can help the team in navigating dates that are assigned by stakeholders (many times without the team’s consent). When someone outside the team sets a delivery, it could be totally unrealistic. That then requires the team to scramble or negotiate a new promised delivery. The Product Owner has to balance the current work, the future work, and help the stakeholders understand a realistic timeline. That could mean in order to plan what comes next there needs to be some research or spike work done.

Dates do matter, but they shouldn’t be the end-all-be-all. Dates are based on estimates and maybe slightly better POCs, spikes, and research. This means delivery timelines should not be considered firm until closer to the delivery date. Delivery dates are important because they establish an expectation of timeline. Trust is essential between the development team and the end-user to ensure the team can deliver on time. To achieve this, every teammate is encouraged to do their part by setting realistic dates that are achievable. This is where a Delivery Lead, Scrum Master, or Project Manager can help. Those performing those roles can help keep the team on track, and also communicate to stakeholders to prevent surprises.

In the world of Agile, dates sometimes matter. There is also important value that can be gained by letting the team have space and time to reduce the unknowns. Dates should be used as a tool to communicate to stakeholders when something might be done, however it should never be considered final until work is actually going into production. Who knows, maybe your development team will surprise you and deliver before the timeline they stated!